Jurors don’t walk into a courtroom as blank slates. They arrive with life experience, instinct, and a limited amount of mental bandwidth to process unfamiliar names, dense exhibits, and competing narratives—often delivered under time pressure. Your job isn’t just to present facts. It’s to help ordinary people understand those facts well enough to make confident decisions.

One of the most reliable ways to do that is simple: organize the story in time.

A strong timeline doesn’t “dumb down” a case. It clarifies it. It reduces confusion, surfaces relationships between events, and gives jurors a sturdy framework to evaluate credibility. Most importantly, it lets them feel oriented—like they know where they are in the story and why each moment matters.

Below is a practical, trial-focused look at why timelines work, how they improve jury comprehension, and how to build timelines that actually persuade.

Why jurors struggle to follow case facts

Even straightforward disputes can become hard to track at trial. That’s not because jurors aren’t paying attention—it’s because the environment is cognitively demanding.

Common comprehension obstacles include:

- Nonlinear presentation: Witness order rarely matches event order. Jurors may hear about the aftermath before the beginning.

- Competing storylines: Each side offers a different “why,” even when the “what” overlaps.

- Information overload: Dates, times, locations, medical visits, emails, text messages, policies, phone calls—stacked quickly.

- Ambiguous labels: “That meeting,” “the incident,” “the second call,” “the revised form”—without anchors, everything blurs.

- Memory limits: Jurors are expected to remember details across days or weeks and then deliberate later.

When jurors lose the thread, they fill gaps using assumptions. That’s risky. If you don’t control the structure, the structure controls you.

A timeline restores the thread.

The mental advantage of chronological structure

Humans naturally process stories in sequence: this happened, then that happened, and because of that, this happened next. When you align your case with how the brain wants to understand events, jurors expend less energy trying to decode the order and more energy evaluating meaning.

A timeline helps jurors:

- Build a “map” of the case

- Place each piece of evidence somewhere specific

- Detect inconsistencies

- Understand cause and effect

- Compare accounts across witnesses

- Stay engaged because they aren’t lost

Chronology becomes a container. Without a container, facts leak.

The hidden jury question: “What connects all of this?”

Jurors rarely ask themselves, “What’s the legal standard?” first. They ask:

- What happened?

- Who did what?

- When did they know it?

- What changed—and why?

- Does this explanation make sense over time?

A timeline answers those questions continuously, without requiring jurors to do extra work.

It also gives jurors a way to test competing narratives. If one side’s story requires improbable timing—instant decisions, missing steps, unexplained delays—jurors feel that friction when events are laid out clearly.

Timelines reduce cognitive load—and that boosts persuasion

Persuasion doesn’t come only from passion. It comes from comprehension.

If jurors are mentally exhausted trying to remember whether Event A came before Event B, they have less capacity left to evaluate credibility, motive, or intent. A good timeline:

- Minimizes confusion by anchoring details to dates and sequences

- Improves recall by tying evidence to a consistent structure

- Creates momentum because the story moves forward cleanly

- Sharpens contrast between “what should have happened” and “what did happen”

This isn’t just about being organized. It’s about giving jurors a smoother path to the conclusion you want them to reach.

The credibility effect: timelines expose contradictions

Contradictions are harder to see when testimony is scattered across hours or days of trial. A timeline brings inconsistencies into the light without you needing to argue about them.

For example:

- A witness claims they reported an issue immediately, but the report appears weeks later.

- A company claims it acted promptly, but key steps are missing in the sequence.

- A defendant claims they didn’t know, but a chain of emails shows earlier awareness.

- An expert assumes a condition existed before an incident, but medical visits show otherwise.

When jurors see the sequence cleanly, they can draw their own conclusions. And conclusions jurors reach themselves are the hardest for the other side to uproot.

Causation becomes clearer when “before” and “after” are undeniable

In many cases, causation is the battlefield.

Timelines help jurors evaluate causation by clarifying:

- Baseline conditions (what was true before the key event)

- Triggering events (what changed)

- Immediate consequences (what happened right after)

- Delayed consequences (what surfaced later and why that delay makes sense)

- Intervening factors (what else occurred that may explain outcomes)

When you control the sequence, you control how jurors think about cause and effect. Not by manipulating—but by making the true relationship between events visible.

Strong timelines improve deliberations

You’re not only presenting to jurors during trial—you’re equipping them for the jury room.

In deliberations, jurors typically:

- reconstruct the story in their own words

- debate turning points (“when did they know?” “what did they do next?”)

- compare testimony to documents

- look for a coherent narrative that fits the evidence

A timeline gives them a shared reference point. It helps them align as a group, resolve disagreements about order, and focus on disputed facts rather than getting stuck in confusion.

In other words: a timeline doesn’t stop working after closing argument. It keeps working when you’re no longer in the room.

What makes a timeline persuasive (not just pretty)

Not all timelines help. Some overwhelm jurors with clutter. Some feel like a data dump. The strongest timelines are both accurate and intentional.

A persuasive timeline is:

1) Selective, not exhaustive

Include what matters. If everything is highlighted, nothing is highlighted.

Ask: Does this event change the story, prove a point, or explain a decision?

If not, it may belong in your internal chronology but not the jury-facing version.

2) Legible at a glance

Jurors shouldn’t need to squint or “study” it like a spreadsheet.

Aim for:

- short event descriptions

- consistent date format

- clean spacing

- limited items per page or panel

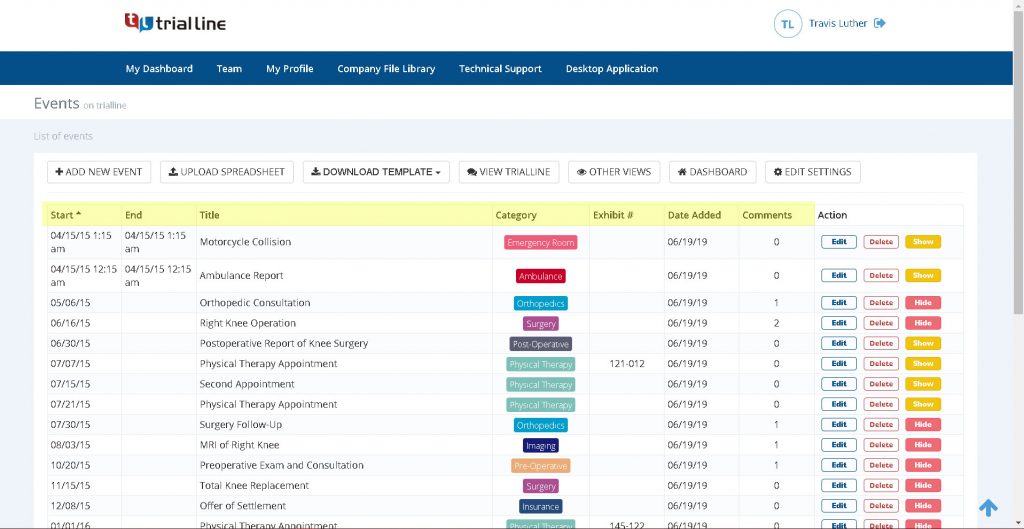

3) Anchored to exhibits

A timeline gains power when jurors can connect events to concrete proof.

Where appropriate, pair key entries with:

- exhibit numbers

- document titles

- witness names

- communication types (email, call, text, report)

4) Built around turning points

A timeline shouldn’t be a calendar—it should be a story.

Most cases have 3–7 major pivots. Examples:

- first notice

- first decision

- first deviation from policy

- escalation

- concealment or denial

- final consequence

When your timeline emphasizes pivots, jurors remember the case in a meaningful way.

5) Consistent with your theme

Your theme is your “why.” Your timeline is your “how it unfolded.”

If your theme is “they ignored warnings,” then your timeline should make warnings—and the lack of action afterward—impossible to miss.

A well-built legal timeline becomes the backbone of that thematic message.

Where timelines fit into trial strategy

A timeline is useful at every stage—if you design it to match the purpose.

Case development

- identify missing documents

- find unexplained gaps

- test whether your theory matches the record

- see where witnesses will help or hurt

Depositions

- lock in dates and sequences

- confront witnesses with contemporaneous documents

- reveal “I don’t recall” patterns around key moments

Motions and mediation

- present a coherent narrative quickly

- show liability or causation clearly

- demonstrate why the other side’s story doesn’t fit the timeline

Opening statement

- give jurors a roadmap before details start flying

- reduce confusion when witnesses come out of order

Direct and cross examination

- keep jurors oriented (“Let’s place this on the timeline…”)

- highlight contradictions cleanly

- prevent the other side from isolating facts out of context

Closing argument

- reconstruct the case in a memorable sequence

- emphasize the turning points and failures

- give jurors a final, coherent story to take into deliberations

A practical method to build a jury-friendly timeline

Here’s a straightforward approach that works across civil and criminal cases.

Step 1: Create the master chronology (everything)

Build a complete internal chronology first—every document date, call, visit, meeting, change, and communication.

Don’t worry about elegance yet. Worry about completeness.

Step 2: Identify the “spine” (the case in 10–20 events)

Now select the handful of events that:

- establish duty/relationship

- show notice/knowledge

- demonstrate decisions and omissions

- connect conduct to outcome

- support damages or consequences

This is the version a juror could retell accurately.

Step 3: Add “support ribs” (optional, only if needed)

If jurors will ask “how do we know that?” add limited supporting entries that:

- corroborate the spine

- explain delays

- clarify a confusing transition

Step 4: Label turning points explicitly

Use simple language:

- “First warning”

- “Policy change”

- “Deadline missed”

- “Escalation”

- “After-the-fact explanation”

You’re not editorializing—you’re guiding comprehension.

Step 5: Pressure test for clarity

Hand it to someone unfamiliar with the case and ask:

- “What happened?”

- “When did things change?”

- “What are the biggest moments?”

If they can’t summarize it, jurors will struggle too.

Common timeline mistakes that hurt comprehension

Even strong cases can suffer from timeline errors. Avoid these pitfalls:

- Overcrowding: too many entries; jurors stop reading

- Inconsistent time units: mixing exact times with vague “early 2023” without reason

- Unexplained gaps: leaving holes where jurors will assume the worst

- Ambiguous phrasing: “discussion,” “issue,” “matter,” “concern” without specifics

- No narrative emphasis: a list of events with no clear turning points

A timeline should feel like a story unfolding—not like a case file spilled onto a page.

Why this matters: comprehension drives confidence

Jurors don’t want to guess. They want to be right.

When they understand the sequence, they feel more confident in:

- identifying who is credible

- deciding what happened

- applying the judge’s instructions

- reaching a verdict they can defend

A strong timeline is one of the clearest ways to help them do that.

Conclusion: organize time, strengthen understanding

The best trial lawyers don’t just argue—they orient. They reduce confusion. They clarify cause and effect. They give jurors a structure sturdy enough to hold the entire case.

A strong timeline does exactly that.

If you want jurors to remember your story, believe your theory, and carry it into deliberations, start by making time visible.